Axial: https://linktr.ee/axialxyz

Axial partners with great founders and inventors. We invest in early-stage life sciences companies such as Appia Bio, Seranova Bio, Delix Therapeutics, Simcha Therapeutics, among others often when they are no more than an idea. We are fanatical about helping the rare inventor who is compelled to build their own enduring business. If you or someone you know has a great idea or company in life sciences, Axial would be excited to get to know you and possibly invest in your vision and company. We are excited to be in business with you — email us at [email protected]

Seven Powers in Life Sciences

Y'all know me, still the same OG

But I been low-key

—Dr. Dre, “Forgot About Dre”

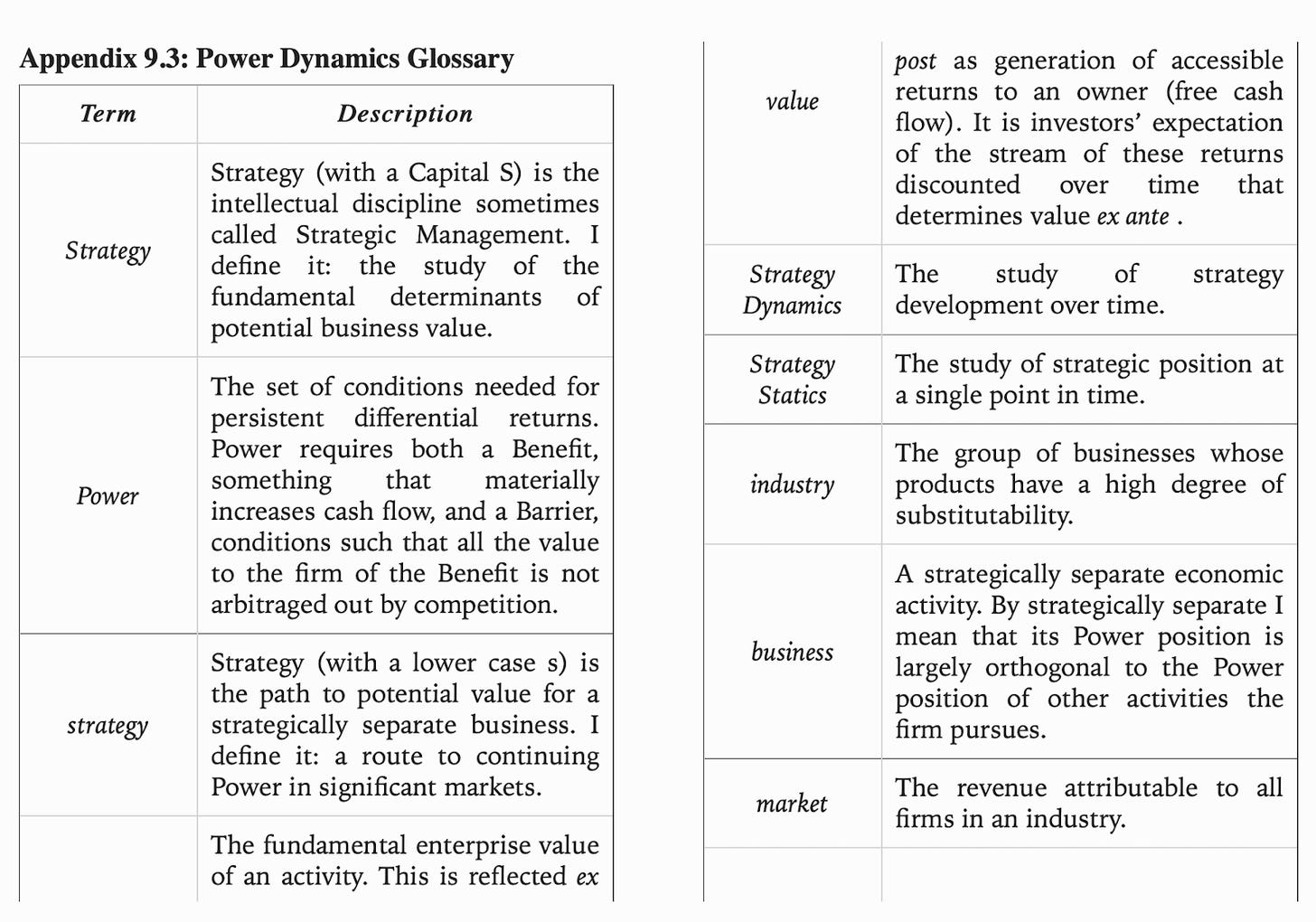

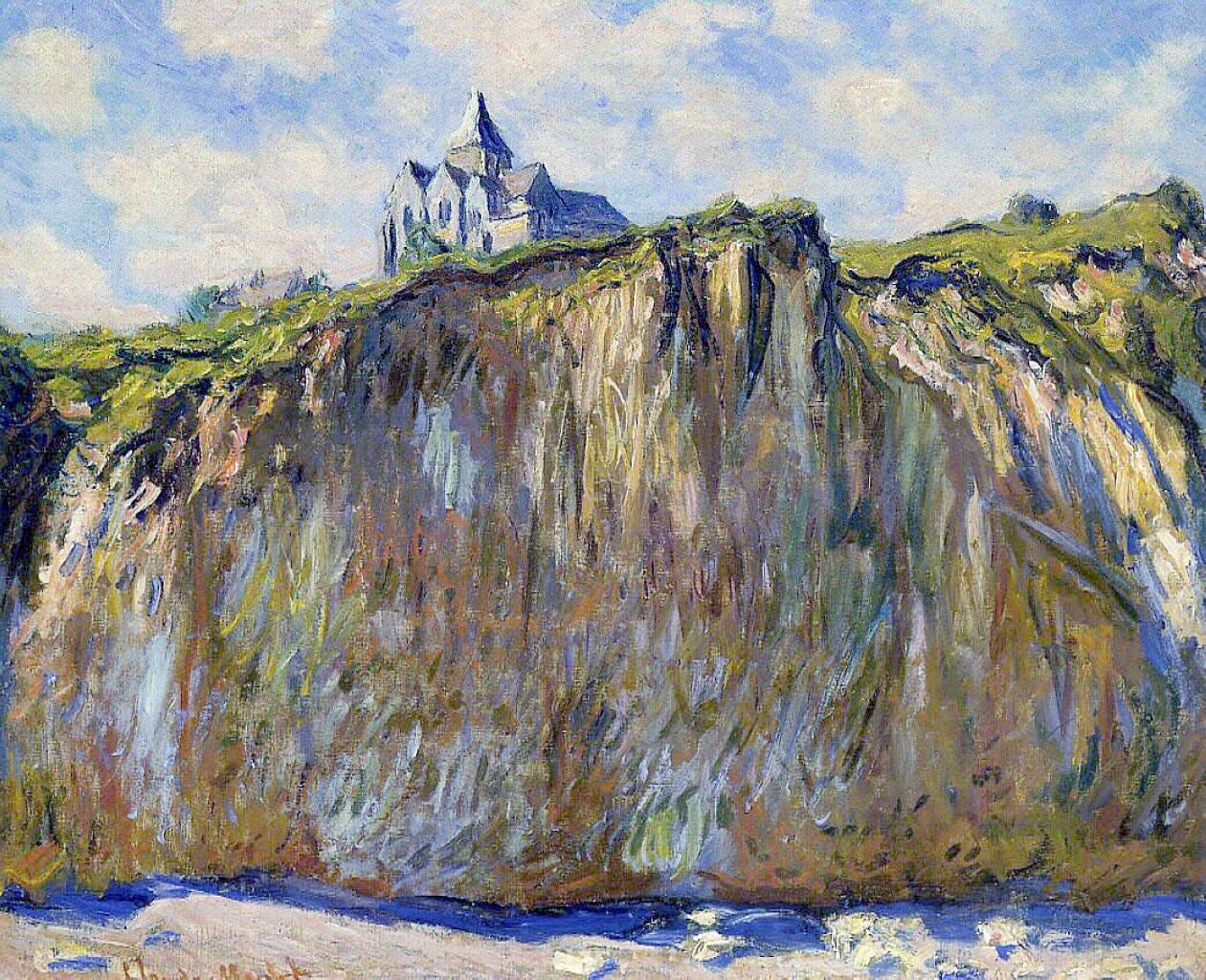

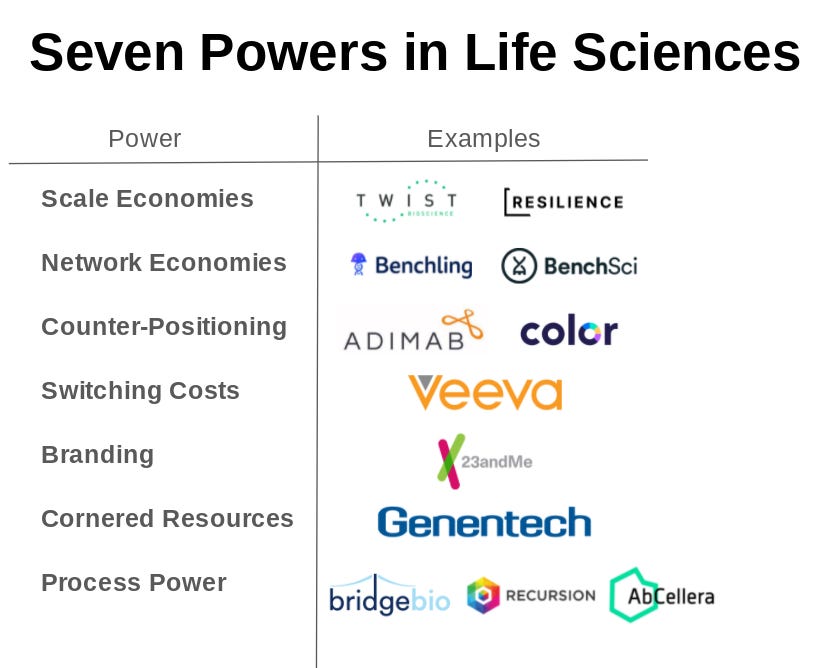

A really useful book for business strategy is 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy by Hamilton Helmer. The book lays out 7 advantages a company can build out and uses various case studies to support each one: scale economies, network economies, counter-positioning, switching costs, branding, cornered resource, process power:

Scale Economies: as production volume increases, the per unit cost of a product decreases. This allows a company to actually create more consumer surplus over time because the fixed cost per user goes down with scale. Companies like Walmart use scale economies to get better supplier deals, Netflix to lower its price for content, Intel to get better manufacturing deals, and Amazon to have lower distribution costs.

Network Economies: the value of the product increases as new users join. This dynamic creates winner-take-all markets. Examples are social networks like Facebook and LinkedIn. The benefits of network economics are twofold - the value of the network imbues pricing power to the company that wields it and makes the costs too high for new entrants to even start gaining market share.

Counter-Positioning: pursuing a business model that would damage an incumbent. New inventions are useful here with Kodak and digital images as an example. Five Guys versus McDonalds is an example of counter-positioning brands. Netflix as one for distribution. And Vanguard versus active investing. This is a powerful strategy for a startup because biases or fear could delay an incumbent’s action and provide time for the former to gain market share. The five stages of counter positioning are: (1) Denial (2) Ridicule (3) Fear (4) Anger (5) Capitulation.

Switching Costs: the loss a customer would experience from switching from one product to another. Oracle for databases is an example. Microsoft for operating systems. This power is very useful to sell a customer additional services but does not help to acquire new ones. There are three main types of switching costs: (1) Financial - money invested (2) Procedural - time to learn how to use the product (3) Relational - personal relationships.

Branding: attributing higher value to an identical product often derived from the product’s past track record of use. Coke is an example. Along with Tiffany’s and Chanel. Strong branding, over decades, creates a positive feedback loop by reinforcing buying.

Cornered Resources: having access to a scarce resource. This could be a new invention, trade secrets, a regulatory exemption or license, or something else hidden. Examples are Genentech and Pixar. Sometimes specific expertise or talent can be monopolized, at least temporarily.

Process Power: when institutional knowledge creates a more productive company. Examples are Toyota and Danaher. One could argue a corporation is a form of artificial general intelligence where the group creates genius from a subset of tasks optimizing for specific goals.

As an extension to this work, where do these 7 powers exist in life sciences?

Scale Economies

Why is scale important? Scale imbues a company with substantial pricing power, the ability to sell more products and build up barriers or at least frustrate even the best of their competition. And why is this important in life sciences especially when a patent is already a strong barrier? Whether you’re developing a drug or inventing a new tool, scale within biotech can give a company multiple shots on goal, an ability to weather binary events, and more.

Economies of scale simply means the declining cost of goods per unit as a business grows, and in life sciences, the classical examples are in biomanufacturing. WuXi’s scale for various services make it extremely difficult to replicate. Resilience got started in 2020 with a substantial amount of capital to quickly gain scale and onshore biomanufacturing. For both of these companies, the dominant costs shift from fixed at small scales to material costs at large scales. There are also examples in services, tools, and emerging ones in drug development:

Reduce the investment requirement over time to grow the business. Example: Resilience and cell & gene therapy manufacturing and Tilda Bio with clinical trials for complex medicines. The building of the railroads in the United States is a strong analogy here; for example, Resilience will have to rely on public-private partnerships similarly to get scale.

Gives the company substantial pricing power. Example: Illumina and sequencing, and Glyphic Biotechnologies working to do the same for proteomics.

Increases cash flow, which can be reinvested to further burnish economies of scale or go into the other 6 powers. Example: Merck and IO. Charm Therapeutics and the entire set of drug developers using machine learning are racing to get scale with the goal of industrializing some parts of the industry.

Make competition unwilling to enter a market. Example: Twist Bioscience and synthesis.

Companies can gain scale with new technologies, massive purchasing orders to lower input costs, a large balance sheet that lowers their cost of capital, a large organization full of specialists that are expensive to hire, distribution, and supply chain integration. The direct benefits are obvious - more cash flow is easier gotten - lowering per-unit costs, increasing margins over time, and reinvesting excess capital into products and platforms. However, the barriers that come with economies of scale might be more important especially in some parts of life sciences, mainly tools and services. In places where the product is or could become a commodity (i.e. DNA, sequencing), businesses have to focus on how to respond to new entrants with their own pricing or peripheral products. So for a new drug company, it might be sufficient just to focus on the technology and market. However, for every non-drug company to succeed and endure, they have to be obsessed about strategy because their businesses could become easily commoditized with little IP protection and less robust ecosystems.

A factory is a good analogy for scale. It takes a good amount of money to get a factory set up but the cost is spread across each unit of goods it produces over time. A “high-tech” factory often requires substantial investments in specialized machinery and methods. On top of this, you might need to bring new specialists on board and retrain your team. This type of work can create a lot of discomfort. Scaling in life sciences is probably harder due to the regulatory overhead and scientific risks. In biotech, there are 3 main types of models for scale: (1) End-to-end, (2) Focused, and (3) Diversified. A life sciences company can work to own an entire process end-to-end from drug discovery to making AAV vectors. This model is appropriate where the process is the product and where you have a first-mover advantage. A focused approach works to maximize optionality, and often in life sciences this is done through licensing. This model works when a good is a commodity, think licensing monoclonal antibodies or biomanufacturing systems. With a focused model, a company can gain scale for a certain category and potentially become a monopoly. Lastly, the diversified model for scale is centered around platforms and partnerships. The goal is to get multiple shots on goal and have capital intensity with less dilution.

In biotech, the goal of scale is to keep on doubling output over and over again to drive costs down. This scale and capital intensity reduces the risk of replication protecting the underlying business. Scale economies are extremely useful for commodity goods. But it might not make sense for luxury and bespoke products. There is always a tradeoff between quality and craftsmanship and economies of scale. And at a certain point, this power can quickly turn into a weakness creating excessive bureaucracy and complacency. Coordination becomes harder and harder and culture gets diluted more and more at scale. BenchSci is one of the most thoughtful companies in the world on culture. They’ve done an incredible job growing their business while protecting themselves from the vulnerabilities of scaling.

Network Economies

Are there network effects in life sciences? Network economies create a business or products that increase in value as more customers use it. So in life sciences, that might mean getting better formulations or reagents with more use of them (i.e. Potion.ai, BenchSci) or protein/DNA design software that gets more useful with a growing user base (i.e. Benchling).

A business with network economies has a product that increases in value. Here, it actually makes sense to charge for a product down-the-line when its value reaches its peak. A good heuristic is demand for your product gets higher as you grow.

Network economies create nearly insurmountable barriers to entry - the price to gain a similar market share is often not profitable (i.e. customer acquisition cost >>> lifetime value of the customer)

Network economies come in 3 major forms: demand-side, supply-side, multi-side. These all just mean what a company focuses on aggregating first. In multi-side network effects, user growth helps another subset of users. Marketplaces, data, physical infrastructure in some cases (i.e. telephone networks) can also benefit from network economies.

The next key question is, where are network effects in life sciences? Historically, strong network effects are predicated on the presence of other networks as long as each network/group is walled off from each other. The submarkets have to be monopolistic, have a wall-offed customer base, and open to a last mover:

Monopolistic - is the market winner-takes-all?

Wall-offed customer base - is there a social or structural barrier between customers and peripheral products or features? For example, a medicinal chemist is unlikely to use a plasmid design tool.

Open to a last mover - have previous companies or products shown a demand from customers but haven’t succeeded in scaling to the entire market?

With network economies, a business’ main advantage is its customer base. With a large enough differential between the leader and the second place company, network economies enable the leader to price well below their competitors while still often maintaining higher margins. With network effects, if a business identifies a monopolistic and wall-offed market, the key to winning is scaling to a point of achieving a wide-enough customer differential - once you’re ahead, you probably stay ahead.

Achieving network economies sounds really attractive in life sciences, and if they are so powerful, why haven’t very large (>$10B) companies been built in the industry. The market sizes are huge in biotech. Maybe most of them aren’t amenable to network effects? At least not yet. Maybe finding markets with several complements could be a useful starting point. Certain applications around antibodies, gene editing, genomics, among others could be open to last movers and be siloed enough for a new company. Finally, ecosystems, similar to Alloy Therapeutics, could be a business model innovation required to bootstrap multi-side network effects in life sciences. Anything else?

Counter-Positioning

The third of the Seven Powers in business is counter-positioning - a new company uses a business model that incumbents cannot pursue without damaging their existing business. So the startup gets protection from larger competitors through collateral damage, real or perceived.

So what are some examples in life sciences?:

In Alzheimer's (AD), most if not all incumbents in neuroscience have their business relying on the beta-amyloid hypothesis. So merely pursuing different pathways is a counter-positioning move in AD.

In cancer diagnostics, the use of PCR-based methods dominated the market for ~2 decades. Companies like Foundation Medicine and Color Genomics did an incredible job to counter-position against incumbents by building out NGS-based tests early. A similar dynamic is occurring in early-stage monitoring right now.

Devoted Health for focusing on aggregating patients rather than maximizing premiums; they make money on ancillary services.

Reference Medicine and creating an entirely new class of biospecimens for drug development, precision medicine, and more.

Adimab and antibody humanization IP where other companies could not use the technology without infringing on competitor’s IP.

Nexilico, Finch Therapeutics, and Nuanced Health for capturing human variation first when developing microbiome therapeutics.

Others? In healthcare, there are major opportunities to use DTC when everyone else relies on distribution partners.

Creating a new business model, especially one with strong counter-positioning, is pretty hard and executing successfully here is rare. Incumbents are often pretty effective at defending themselves either through marketing or scale. But cognitive biases really enable counter-positioning to work in business. Does an incumbent keep on doing business as usual and give up market share to a new company? Or do they shift their business model and risk losing revenue from their existing model? This is a tough decision because the loss is known but the gain is unknown. Due to loss aversion, the larger company will often do nothing while the startup continues to grow with its innovative business model. There’s also agency and career risk. If you’re leading or working at a big company, recommending major shifts in the business model can lead to you losing your job. This is why combining type A personalities with an ability to take social risk is a great profile for founders - especially in biotech, these types of individuals will push the limits on what their business can do. As a result, new business models are the consequence of the convergence between markets, technologies, and founders. Some of the key themes for counter-positioning are:

Opportunities for counter-positioning exist from changing technology landscapes, consumers having misinformation, and poor incentives in product distribution

The company with the new business model serves more and more customers until it is too late for the incumbent to have any shot at switching over

The new, heterodox business model often has lower costs or some sort of pricing power/premium product. It’s even better if the model allows a company to give away a product(s) for free - commoditizing your complement is pretty powerful.

Incumbents perceive collateral damage of pursuing a new business model too high

Or incumbents don’t have the technical capabilities to pursue it

Product moats are stronger than financial moats

A committed founder to have the courage to pursue something different

Ultimately, biotech needs more business model innovation. To lower the costs of products, increase scale, and more. Counter-positioning gives the entrepreneur a tool to compete with giants.

Switching Costs

The fourth of the seven powers in business is switching costs, which is the loss a customer will experience from switching over from the product they are using to another one. This power is actually pretty widespread in life sciences. If you think switching enterprise software is hard, switching a biomanufacturing protocol, an EHR in healthcare, or a diagnostics workflow is a lot harder to switch over. Regulation in combination with the complexity of biology and medicine have allowed many biotech companies to grow substantially due to switching costs.

The hard part about getting this power as a moat is getting the customers in the first place. Either you have to knock off an existing product or pursue an entirely new market and wait. However, once you do get switching costs, they imbue long-term pricing power to your business and can give you the ability to defend yourself relatively quickly.

This power is divided into 3 subclasses:

Financial - the money required for switching (i.e. switching over to a new plasmid editor and having to bear the costs of the new software, onboarding, and complementary services).

Relationships - losing personal and business relationships as well as brand association from switching over. Great sales people become advisors to their customers on more matters over time.

Procedural - this is the hardest of the subclasses to define and may be the most important for a business; the risk of switching from the familiar to the new, riskier, and uncertain product. Doing something new especially at a large corporation where billions may be on the line is scary. Becoming a familiar product and brand ultimately might create the strongest switching cost. Veeva is the best example in life sciences of this. The company used its product lock-in to gain economies of scope and expand its product portfolio.

What are the downsides to switching costs? This might be the most seductive business power and as a result might create fatal weak points in a business:

Shifts in technology can make a product obsolete and your business might not recognize this or want to change until it’s too late

Organizational laziness because the sales team, product people, and beyond kind of know the customers are not likely to use new products so they become less concerned about their needs

But if a good leader, often a founder, can keep the company ahead of the technology curve and their company focused on the customers, switching costs are often a springboard to aggregate more customers to commoditize more complements. By executing this strategy, the business can find new markets beyond your current sandbox and move into using branding as a business power.

Branding

The fifth of the seven powers is branding. What is a brand? For me, this is the hardest power to truly understand. A brand seems to have a long-term track record (i.e. reinforcing actions) around quality and experiences (i.e. evoking positive emotion) that enables a business or product to be perceived as higher value than equivalents. I think I’ve learned the most about branding from reading David Ogilvy. As a side note, before becoming an advertising legend, he farmed with the Amish. For brands, the long-term track record part can be taken from others through association as well. An example is Apple associating itself with Gandhi and MLK early on. In biotech, associating with former Genentech employees or cancer biologists from MSKCC is similar. Brand provides benefits to a product mainly in two ways:

Effective valence - the feeling from the brand that generates a positive feeling detached from the actual value of the product. This is why virtue signalers can be successful in the short-term even if they don’t do anything useful for their customers.

Uncertainty reduction - customers get what they expect from a brand they know. One in the hand is often better than two in the bush.

What is branding in life sciences? To me, it seems kind of non-existent right now. Brands haven’t really matter in biotech. Patents suffice. However, customers probably still buy aspirin from Bayer due to past safety mistakes around manufacturing and formulation by other companies. Even in drug development, brands and patient perception are important albeit ignored by most for now - there are opportunities to differentiate beyond clinical benefits and target patient populations for their specific needs with features like duration and onset to action. This gap creates opportunities for startups to develop brands across life sciences and healthcare. The combination of social media and more consumer awareness around things like climate change and the healthcare system, has led to some growth of biotech/healthcare companies centered around a brand. Virta Health, Sami, and the entire team have done legendary work to build the iconic brand for T1D patients. 23andMe built a brand, and a new market category, around DTC genomics. Cella Farms for bread and much more. Rubi Laboratories for sustainable textiles. Revela for hair growth and more. And Bristle Health for oral health. The goal of all these companies is to build great products and to win the hearts and minds of their customers.

Biology allows one to more easily version physical products and when combined with a brand, allows a company to keep prices steady or even raise them if their product improves with each new version. However, companies growing this power have to be aware of brand dilution, geographic/cultural limits, changing preferences from their customers, and counterfeiting. The use of branding is still very early in life sciences. But as consumer products from biology (i.e. pet dragon) become more and more widespread, branding will become a lot more important in the industry.

Cornered Resources

The sixth of the 7 powers is cornering a resource. In biotech, this is the most widespread power in use. Patents, trade secrets, regulatory capture are key advantages in the industry. Talent and distribution are important as well but have become a little harder to monopolize. In short, cornering a resource in life sciences is often as straightforward as having a strong set of patents. So hire the best counsel you can afford and leave it at that.

Alnylam and RNAi is one of the best examples of this power. Robert Millman did a lot of the heavy lifting early on to make sure Alnylam had the strongest IP position in the field, which allowed the business to survive extreme ups and downs. Genentech cornered the market for many classes of biologics in the 1970s and 1980s. Seranova Bio is doing something similar for autoantibodies right now. Cornering a resource relies on having a unique method to discover new ideas, people, and inventions. In drug development, this is often done through specific modalities or disease areas. For other life sciences fields, cornering a resource is probably not that feasible.

Process Power

The last of the seven powers is process power. And my favorite one. This is an advantage within a company that leads to a better product or lower costs. Think of the design team at Apple or the DBS team at Danaher, respectively. This power is a lot different than just good execution or operations Process power is centered around creating operational barriers that require time and tacit knowledge for others to surmount.

Toyota is an incredible example in car manufacturing. Danaher was actually inspired by Toyota and repurposed the Toyota Production System for industrials and now molecular diagnostics. Danaher and Toyota’s systems rely on complexity from logistics, manufacturing, and various process improvements. Over time, through tinkering and trial and error, these systems evolve and improve, which generates tacit knowledge that is passed on through the organization.

Where does process power exist in life sciences? WuXi is probably the best example. They offer low cost biopharma services at scale. Their power is a consequence of 2 decades of improvement and an ever growing complex web of customers and partners. Danaher is another example with their ownership of Beckman Coulter and Cepheid. Aperiam Bio for enzyme design. EQRx is building up a similar power through the data and clinical know-how to quickly become a fast follower in drug development. AbCellera becoming a one-stop shop for biologics discovery. Recursion Pharmaceuticals building an assembly line for new medicines. Enable Medicine, Replay Therapeutics, and BridgeBio building outsider moats in their respective disease and technology areas. Any others?